Ancient Iwi

According to Māori oral traditions, the earliest peoples to inhabit Te Waipounamu were tribal groups known as Hāwea, Rapuwai, and Waitaha, who inhabited the island for centuries before the arrival of more recent tribal migrations of Ngāti Māmoe, Ngāti Wairaki, and Ngāi Tahu. The early moa hunting tribes are believed to have been established in Canterbury about one thousand years ago.

Hāwea

Today, little is known of the traditions of Hāwea and where they originated from.

It is said that they were the first tribe to settle on the South Island. Chief Taiehu and his axe was Āwhioraki. Waka: Kapakitua. A very dark people with thick, curly hair and strong white teeth.

Tipuna: Hawea-i-te-raki, the son of the chief Waitaha-Ariki (p. 21; Traditions and Legends of Southern Māori, J Beattie.)

Te Rapuwai / Rapuai / Ngā ai Tanga a te Puhirere / Te Mano o te Rapuwai

Originally from the North Island, the second tribe to settle in the South Island. Copper and ginger-coloured hair, but of Polynesian descent.

Their history and traditions have not persisted, and it is believed that over time they were readily absorbed into Waitaha.

The Rapuwai people lived at the head of the Ōhou lake in Canterbury. One of the districts they most densely populated is about Lake Kaitangata, in the Otago Province, and that district is sometimes called, in consequence, “Te Mano-o-te-Rapuwai.” One of their most populous villages was Te Ika-maru, which is said to have been named after a great chief. A sub-tribe of Rapuwai is said to have been Kāti-koko, and an interesting legend is told of these people. They went round to the Sounds, found a huge piece of greenstone in the sea, and set out to drive it round to the Bluff. Three canoes followed it—one on each side and one behind—and yet it nearly eluded them several times. They nearly got it ashore at Ōraka (five miles west of Riverton), but it dodged on till it settled where it is, and it now forms Motupiu (Dog Island, off the Bluff).

Hapu: Kāti Koko

Waitaha / Te Kapuwai

It is known that the more recent tribal grouping of Waitaha originated from the east coast of the North Island. Major Waitaha settlements in Canterbury were established at Puari Pā and at Pegasus Bay.

Recent excavations have been carried out at the site of a new township called Pegasus, which has been built near the Ashley (Rakahuri) River. The archaeological work carried out has revealed an extensive site believed to be 500–600 years old. Hundreds of artefacts have been found, including numerous pounamu items, which indicate that this area was a significant pounamu working site over a long period of time. This Waitaha pā is close to Kaiapoi pā, the home of the Ngāi Tūāhuriri chief Tūrākautahi.

Today, Waitaha traditions remain an integral part of Te Waipounamu through the names given to geographical features, rivers, and coastlines of this large island by these inhabitants.

They were the third tribe to settle on the South Island between 1477 and 1577. They also had Pā at the mouth of the Molyneux River, Lake Te Anau, Lake Wakatipu, and Ōamaru.

Ōtaraia bears the name of a Waitaha chief. Waiwera is named after Waiwhero, a Waitaha Chief. Te Anau and Aparima after chieftainesses.

Not was not as dark-skinned as Hāwea and had long, straight hair.

Waka: Uruao, also known as Te Waka a Rangi

Hapū: Kāti Rākai

Chief: Rākaihautū

Kāti Māmoe / Hotu Māmoe

The fourth tribe to settle in the South Island occurred in 1577–1677, prior to Kāi Tahu conquering all previous iwi.

Hapū: Kāti Rākai, Kāti Hinekato (Edward Shortland)

Other ancient Iwi

This information is from The Oral Traditions of Ngāi Tahu page 17.

Ngāti Wairaki

Ngāti Tūatakōkiri

This information is taken from Tikao Talks.

Kahea: is an ancient tribe that perhaps Māmoe and Waitaha are offshoots of. Taare Tikao mentions that Te Maiharoa was a descendant of Kahea.

Kāti Matamata pg. 42 Tikao Talks. It is briefly mentioned that one person may be living at Port Levy and one in Tuahiwi. pg. 405 of Traditional Lifeways of the Southern Maori by Herries Beattie states the likely whānau of Kāti Matamata

Kāhui Tipua: The first inhabitants of the south island were said to be giant ogre-like people. They were a hapū of the Maeroero Iwi. Tipuna: Tara. Rapuwai conquered them.

Kāti Ira: near the top of the South Island.

Kui: An ancient race so denominated; they are said to have been a people of short stature who inhabited New Zealand after Maui visited it. Page 42, Māori Place Names of Canterbury. H.Beattie.

Maeroero / Maeroero-Rapuwai: lived in the bush and would fish with their finger nails in the shallow bays. They would warn Māori not to come too close. They played their flutes near Akaroa. Descendants of Rapuwai lived on the Banks Peninsula until the arrival of the Pākehā.

Māoriori: According to Taare Tikao, this Iwi was in the South Island for about 100 generations before Hāwea. There were two hapu of this tribe called Kui, Kae, and Tutumaiao.

Patupairehe: They would play their flutes, and their flashing lights could be seen on the mudflaps. They lived on the Banks Pensinsula until the arrival of the Pākehā.

Pounemu were an ancient tribe who fled Hawaiki from two other tribes, Hoaka (grindstone) and Mata (flint). All three tribes were in the South Island. Pounemu waka is the Tairea. Hoaka and Mata iwi came in the Āraiteuru waka.

Tini-o-te-para-rakau the iwi of Wahie-roa, the father of Rata.

Kāti Raka (pg 21 Traditions and Legends of Southern Māori J Beattie.)

Pohatu-Parimurimu (pg 21 Traditions and Legends of Southern Māori J Beattie.)

Te Aruhe-Taratara (pg 21 Traditions and Legends of Southern Māori J Beattie.)

Te Raupō-Manu (pg 21 Traditions and Legends of Southern Māori, J Beattie.)

Te Rākau-Tipu (pg 21 Traditions and Legends of Southern Māori J Beattie.)

Te Rākau-Hape (pg 21 Traditions and Legends of Southern Māori J Beattie.)

Kāhui Roko; Hapū: Roko tuatahi, Roko-i-tua, Roko-i-pae, Roko-i-te-aniwaaniwa, Roko-i-he-haeata. Chief: O-roko-i-te-ata (pg 21 Traditions and Legends of Southern Māori J Beattie.)

Ngāi Tahu Hapū

Within Ngāi Tahu there are now five primary hapū: Kāti Kurī, Ngāti Irakehu, Kāti Huirapa, Ngāi Tūāhuriri and Ngāi Te Ruahikihiki.

Below is a list of some of the traditional (or pre-settlement) hapū names of Kāi Tahu.

|

Hāwea

Hinekura (Kaikōura)

Kāi Tara

Kāi Kahukura/Kai Te Kahukura (Tuahiwi)

Kāi Tangata

Kāi Taoka

Kāi Tarawa

Kāi Tarewa (Akaroa)

Kāi Te Aotaumarewa

Kai Te Atawhuia (Kaiapoi)

Kāi Te Makahi

Kāi Te Pahi

Kāi Te Raki

Kāi Te Rakiamoa

Kāi Te Rangi

Kāi Te Rangitamau

Kāi Te Urupaoa

Kāi Tūāhuriuri

Kāi Tuaki

Kāi Tūhaitara

Kāi Tuke

Kāi Tuna

Kāi Tūteahurewa

Kāti Hapūiti (pp. 93 and 94, Canterbury Place Names)

Kāti Hāteatea

Kāti Hāwea

Kāti Hikawaikura

Kāti Hikoa

Kāti Hikoata

Kāti Hinekakau

Kāti Hinekato

Kāti Hine Kura (Kaikōura)

Kāti Hine Matua (Bluff)

Kāti Hinemihi

Kāti Hinetewai (Half Moon Bay)

Kāti Huikai

Kāti Huirapa

Kāti Ira

|

Kāti Irakehu/Kāti Irekehu (Banks Peninsula)

Rongokako

Kāti Kane (Country from the Waitaki south to Shag Point and inland to Lakes Hāwea and Wānaka)

Kāti Karehu

Kāti Kaweriri

Kāti Kopihi

Kāti Koreha (Their old pā stood back on the old coach road north of the Ahuriri Lagoon.)

Kāti Kuia

Kāti Kura

Kāti Kurī

Kāti Kūware

Kāti Māhaki

Kāti Makō

Kāti Māmoe

Kāti Matamata (Kāti Māmoe)

Kāti Mihi

Kāti Moki (Taumutu)

Kāti Mū

Kāti Pahi

Kāti Rahui

Kāti Rakaihautu / Kāti Rakai

Kāti Rakaimamoe

Kāti Raki (pp. 93 and 94, Canterbury Place Names)

Kāti Rakiāmoa

Kāti Rakiwhakaputa

Kāti Rokomai

Kāti Ruahikihiki

Kāti Tahupōtiki

Kāti Tairewa

Kāti Tamahaki

|

Kāti Te Aohikuraki

Kāti Te Atawhiua

Kāti Te Rakiāmoa

Kāti Tepaihi

Kāti Tū

Kāti Tūahuriri (Tuahiwi)

Kāti Turakautahi

Kāti Tuteahuka (Kāiapoi)

Kāti Urihia

Kāti Waewae (West Coast)

Kāti Wairaki (West Coast)

Kāti Wairua

Kāti Wakakaha

Kāti Whae

Kāti Whaea

Kāti Whaitara

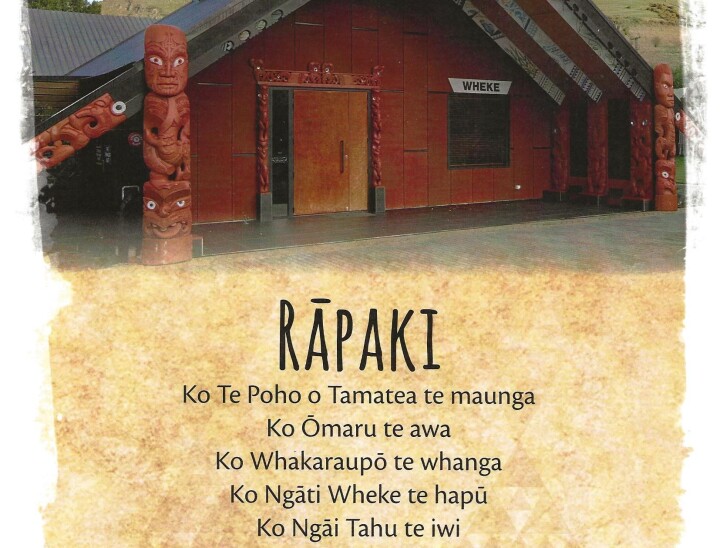

Kāti Wheke (Rāpaki)

Kāti-Tumatakōkiri

Taupōnui

Tura

Te Ahuriri

Te Aitaka a Tapuiti

Te Ana o Kātiwairua (Māmoe Hapū)

Te Ataumarewa

Te Au Taumarewa (Moeraki)

Te Rakiwhakaputa

Tuteuhuka

Uenuku

Kāti Whata (Waimea)

Kāti Rua (Waimea)

Kāti Ruatapu (West Coast)

Kāti Kawerirī

Ngāi te Aotaumarewa

Poupoutunoa (Canterbury)

Kāti Rakiora (Canterbury)

Ko Ngāi-te-rua-wai (pp. 93 and 94, Canterbry Place Names)

Ko Ngāti Hinewairaki (pp. 93 and 94, Canterbry Place Names)

Ko Ngāti-paro-paro (pp. 93 and 94, Canterbry Place Names)

Ngāti Kaweriri (pp. 93 and 94, Canterbry Place Names)Kāti-paroparo near Cave in Orari hills (Canterbury Place Names pg 114, A mixed Waitaha-Kāti Māmoe) |

Ngāi Tahu – Who We Are

Ngāi Tahu means “people of Tahu” and all Ngāi Tahu whānui can trace their ancestry back to this man, the tribe’s founder, Tahu Pōtiki.

Our defining link as Ngāi Tahu is the ability to whakapapa back through this history and link with our ancestors of the past. This brief history gives an overview of where we come from which hopefully does not diminish the rich tapestry that is our history.

Ngāi Tahu are the Māori people of the southern islands of New Zealand—Te Waipounamu – the Greenstone Isle. We hold the rangatiratanga or tribal authority to over 80 per cent of the South Island. Our histories begin as with all Māori when the first settlers of Polynesia colonised Tonga, from the west, about 1500 BC. Over the next 2000 years their descendents colonised the remainder of Polynesia, starting with Samoa, then moving on to the Marquesas (about 2000 years ago), Tahiti (1500 years ago) then on to Easter Island, Hawaii, New Zealand and the Chathams. They found New Zealand uninhabited but full of wonderful new food sources. Some of the features typical of this period are moa-hunting and sea-mammal hunting economy, supplemented by crops of root vegetables.

Archaeology reveals that settlements were predominantly coastal, probably for the proximity to their major food source, the ocean. As a result of population pressure about 500 – 800 years ago, settlements became more widespread and regional differences began to appear perhaps relating to the development of different tribal groups. The first real evidence of tribal warfare comes from this period with the appearance of various weapons and the construction of fortified pā sites (settlements).

The Ngāi Tahu people have their origins in three main streams of migration. The first of our people to arrive in the southern islands migrated here under the leadership of Rākaihautū on the waka (canoe) Uruao. They arrived in Whakatū, Nelson and proceeded to explore and inhabit the South Island. This is the origin of the Waitaha iwi, who named the land and the coast that borders it.

The plentiful resources of Te Waipounamu called others to abandon their northern homes and move southward. The second wave of migration was undertaken by the descendants of Whatu Māmoe who came down from the North Island’s east coast to claim a place for themselves in the south. These descendants came to be known as Kāti Māmoe and through inter-marriage and conquest these migrants merged with the resident Waitaha and took over authority of Te Waipounamu.

Continuing the link with the east coast of the North Island, Paikea landed in the Bay of Plenty and fathered Tahu Pōtiki.

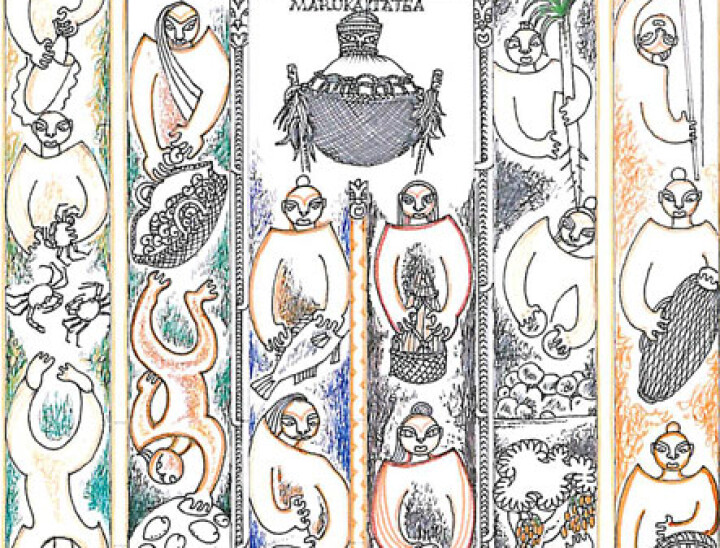

The descendants of Tahu Pōtiki who formed Ngāi Tūhaitara and Ngāti Kurī moved south travelling first to Wellington. Ngāi Tūhaitara and Ngāti Kurī settled in Te Whanganui-a-Tara (Wellington) under the respective leadership of Tū Āhuriri and Maru Kaitātea.

Ngāti Kurī and Ngāi Tūhaitara migrated to Te Waipounamu. Maru Kaitātea established Ngāti Kurī at Kaikōura. Tūāhuriri’s son, Tūrākautahi, placed Ngāi Tūhaitara at Kaiapoi Pā. With Kaikōura and Kaiapoi Pā established, and through intermarriage, warfare and political alliances, Ngāi Tahu interests amalgamated with Ngāti Māmoe and Waitaha iwi and Ngāi Tahu iwi established manawhenua or pre-eminence in the South Island. Sub-tribes or hapū became established around distinct areas, and have become the Papatipu Rūnanga that modern day Ngāi Tahu use to exercise tribal democracy.

Pēpeha – Tribal Proverb / Sayings

Ko Aoraki te waka Atua – Aoaraki is the godly canoe

Ko Uruao te waka Tipua – Uruao the supernatural canoe

Ko Kurahaupo te waka takata o taku rahi – Kurahaupo the canoe of our people and importance

Whatoka ki te ihu, ruatea ki te riu, popoto taku tipuna ki te uruki e! – Whatoka at the bow, Ruatea at the hull, my ancestor Popoto navigates!

_______________________

“Mō tātou, ā, mō kā uri ā muri ake nei…” For us and our children after us…

Whakataukī Ngāi Tahu – Ngāi Tahu Proverbs

1.Huriawa Karamea, Huirapa Kōkōwai, He kura huna ko karo Kāhore ia, Kāhore ia hī.

The clay from Huriawa preserves our ancestral house. Will our knowledge be lost, Never! Never!

2. Ko ō mātou kāinga nohoanga, ko ā mātou mahinga kai, me waiho mārie mō ā mātou tamariki, mō muri iho i a mātou.

Our places of residence, cultivations and food-gathering places must still be left to us, for ourselves and our children after us. Kemps Deed.

3. Ko te toa i a tini i a mano o te tangata”

Tūwhakauika & Te Oreorehua – We possess the strength of the many. It is the bravery of a multitude, of thousands of people.

4. Hāhā te whenua, hāhā te tangata.

Desolate land, desolate people.

5. He mahi kai takata, he mahi kai hōaka.

It is work that consumes people, as greenstone consumes sandstone.

6. He manawa tahi, he manawa ora, he manawa toa, te manawa Kāi Tahu.

A united heart, a vibrant heart, a determined heart, this is the heart of Kāi Tahu.

7. Kauraka koutou i mate pīrau pēnei me au nei. E kāore! Me haere ake koutou i ruka i te umu kakara. Taku whakaaro i mate rakatira i ruka i te tāpapa whawhai.

Do not die a rotting death like mine. No! Leave this world via the fragrant ovens of war. In my opinion a chiefly death occurs on the battlefield. On his deathbed, Te Wera, a renowned Kāi Tahu fighting chief, warned his sons to die honourably on the battlefield and not slowly of natural causes, as was his fate.

8. Kei korā wā kei Motupōhue, he pāreka e kai ana, nā tō tūtae.

It was there at Motupōhue that a shag stood, eating your excrement.

9. Kia pai ai taku titiro ki Te Ara a Kiwa.

Let me gaze upon Foveaux Strait.

10. Ko ngā hau ki ētahi wāhi, ko ngā kai ki Orariki.

Whatever the season or wind, food will be found at Orariki.

11. Ko te kāhui mauka, tū tonu, tū tonu, ko te kāhui takata karo noa, karo noa ka haere.

The people will perish but the mountains shall remain.

12. Te kopa iti a Raureka.

The tiny purse of Raureka. This refers to a female ancestor, Raureka, who travelled from the West Coast in pursuit of a lost dog. She encountered people in the South Canterbury region and took from her purse the pounamu, or greenstone. This pepeha is used to denote something precious.

13. Ko te mauka ko Te Whatarama, te manu o reira, he kākāpō. Mōku tēnā mauka kia maro ai a Hine-mihi rāua ko Hutika.

Te Whatarama is the mountain of parrot and will be mine to cloak my daughter Hinemihi and Hutika.

14. Takaroa pūkunohi nui.

The god of the sea Takaroa can observe all we are doing.

15. Te Puna Waimarie, Te Puna Hauaitu, Te Puna Karikari.

The pools of frozen water; The pools of bounty; The pools dug by the hand of man. On arrival in this new land, Rākaihautu sought an indication of the nature of the land and the fortunes that awaited him and his people. With his digging stick he made three pools and then gave the prophetic utterance about what lay before them.

16. Tūrākautahi: Ko Kura-tāwhiti te mauka kākāpō, ko au te takata.

Kura-tāwhiti is the mountain that has the parrot and I am the man.

17. E tā mā, haramai rā, kia komotia ō koutou ihu ki roto i Taratu.

Come here sirs, and we’ll bury your noses in Lake Taratu. This was the challenge of Ngāi Tahu at Kaiapoi as Te Rauparaha was trying to breach the pā’s defenses. The metaphor of the nose being submerged or above water is stiff current. Above water is taken to mean survival and progress; below water is suffering death. (Ngā Pēpeha a ngā Tīpuna).

18. Haere e oma kia puta ai koe.

Go, run in order that you may escape.

The saying comes from the story of Tūāhuriri. He ordered the ambush of people from Kaikōura. When the people of Moeraki heard of this, they sent a war party to take revenge who entered the village of Tūāhuriri and took the people prisoner. Kūwhare was held apart by order of a young chief to be killed by him, but was able to escape but was perused by a noted runner. The runner called out to him the above, which is now the whakataukī. (Ngā Pepeha a ngā Tipuna: White 1887: III.111)

19. Haere, e te hoa, ko tō tātou kāinga nui tēnā.

Go, o friend, for that is the great abode for us. A poetic farewell fitting for the funeral obsequies. (Ngā Pēpeha a ngā Tīpuna: Davis 1974: 58)

20. Haere mai, e te Rāwhiti.

Welcome o sunrise. A traditional greeting of the South Island to the North Island.

A reference to the fact that each day the sun first reaches Hikurangi. (Ngā Pēpeha a ngā Tīpuna: Smith 1913a:113)

21. Te Whakatakanga o te Ngārehu a Tamatea.

The preparation of Tamatea’s charcoal.

This allusion to the tattooing of Tamatea was used by Kāi Tahu when referring to the people of Murihiku. (Ngā Pēpeha a ngā Tīpuna: Anderson 1942:183; Cowan 1905: 195).

22. He Puna Hauaitu; He Puna Waimaria; He Puna Karikari a Rākaihautu.

The pools of frozen water; The pools of bounty; The pools dug by Rākaihautu (Te Kete Ako a Rākaihautu).

23. Hakahaka Te Raki i ruka nei, ko te po koua tupu.

Though the heavens hang low there is growth in the dark. Two Ngāi Tahu chiefs whose tribe faced annihilation used this phrase. Also appears at the start of Ngāi Tahu whakapapa to the creation chants, which indicates that from darkness life emerged. (Ngā Pikitūroa o Ngāi Tahu. The Oral Traditions of Ngāi Tahu. (Ngā Pikitūroa o Ngāi Tahu: Page 79.)

24. Tokotoru a te tuakana, tokotoru a te taina, ko ngā tokoono ēnei a Hemo i noho ai i Tūranga.

‘Hemo the mother of Ngāti Porou and Ngāi Tahu – all who came from Tūranga. (Christchurch City Libraries, ‘Tūranga – Our Māori name’).

25. Te Whatu-Kura a Takaroa.

A flattering and figurative allusion to a high-born girl. (Tikao Talks: page 28).

26. Ko mate te marama. A saying when the moon disappears away. (Tikao Talks: Page 44).

27. Ka tō te rā. The sun is setting. (Tikao Talks: Page 46)

28. Ngā rā o Toru Whitu.

The sun from July to November (Tikao Talks: Page 46).

29. Ko tō te rā.

The sun has set (Tikao Talks: Page 46).

30. Whatutaki te marama ki te rā.

Reference to an eclipse of the sun. (Tikao Talks: Page 48).

31. Ko te kete ika a Tutekawa.

A reference to the large amount of fish in Lake Forsyth and Lake Waihora/Ellesmere. (Tikao Talks: Page 129).

32. Te hauka te ahi.

A reference to a stranger who stays longer will get to know the hosts better. (Tikao Talks: Page 152).

33. O te parara.

A derogatory term for a Māori person of mixed descent. The saying implies the person’s mother was paid for intercourse that produced the offspring. (Tikao Talks: Page 155).

34. Ko Waitaha kua Ngāti Māmoetia, kua Ngāi Tahutia.

(Waitaha were absorbed by Ngāti Māmoe who were in turn absorbed into Ngāi Tahu).

35. Te kōkopu, te kai o Maui.

The kōkopu, the food of Maui. pg 10 Moriori : the Morioris of the South Island by Herries Beattie

36. Te hao te kai a te aitaka a Tapu-iti.

That the small delicious eel known as hao is the favourite food of the descendants of Tapu-iti, who was the wife of Te Rakihouia. pg 32 Moriori : the Morioris of the South Island by Herries Beattie

37. Ka-poupou-a-Te Rakihouia.

The whole Canterbury seaboard is known as. Lit. the posts of Te Rakihouia. Because that chief erected posts at the river-mouths to enable eel weirs to be built. g 32 Moriori : the Morioris of the South Island by Herries Beattie

38. Ka-whata-kai-a-Te Rakihouia.

The sea cliffs along the east coast. Lit. the food storehouses of Te Rakihouia. pg 32 Moriori : the Morioris of the South Island by Herries Beattie.

39. Whata-tū-a-Te Rakihouia.

The sea cliffs along the east coast. Lit. the standing storehouses of Te Rakihouia. Because the son of Rākaihaitū procured food from them. pg 32 Moriori : the Morioris of the South Island by Herries Beattie.

Rakiura – Stewart Island

Rakiura ‘glowing skies’

It was named this after ‘Tahu-nui-a-rangi’ or ‘Ngā Kurakura o Hinenuitepō’ the ‘southern lights’ or ‘aurora australis’.

It it also know by other names:

Motunui ‘big island’

Te Punga o te Waka o Māui ‘the anchor of the waka of Māui’

Stewart Island to Pākehā

At 1,680 km2, it is our thirs largest island.

Halfmoon Bay on the north-east coast is 39km from Bluff.

Te Ara a Kiwa – Foveaux Strait

Kiwa’s pathway and Kewa’s lost tooth

Māori knew Foveaux Strait as Te Ara a Kiwa (the pathway of Kiwa). Kiwa was an ancestor who tired of crossing the isthmus which, according to the story, then connected Rakiura to Southland. He asked the whale, Kewa, to eat through the land to create a channel so Kiwa could cross by waka. Crumbs that fell from the whale’s mouth became islands in Foveaux Strait. Solander Island (Hautere), which guards the western approaches of the strait, was also known as Te Niho a Kewa, a tooth lost from the whale’s mouth.

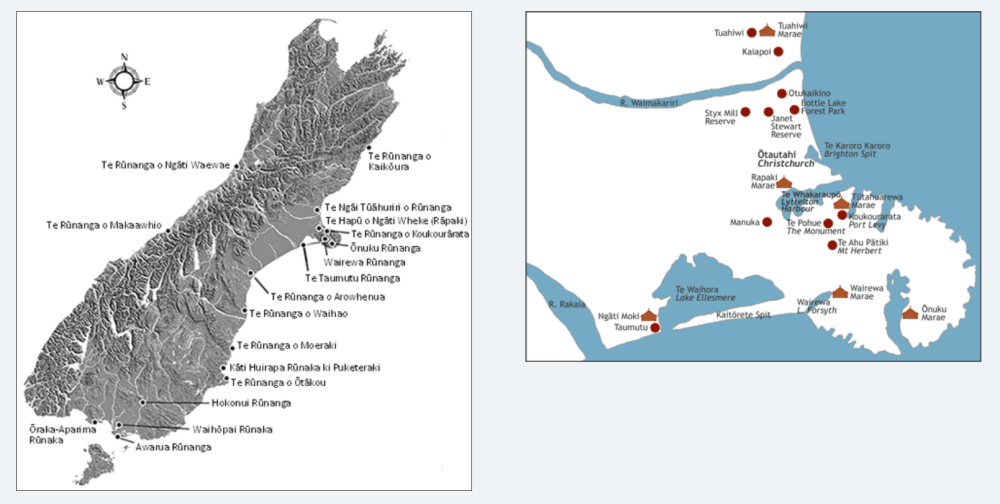

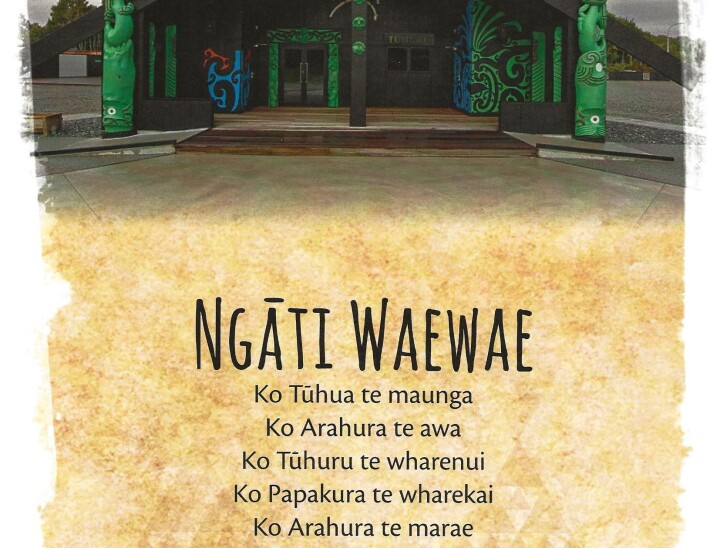

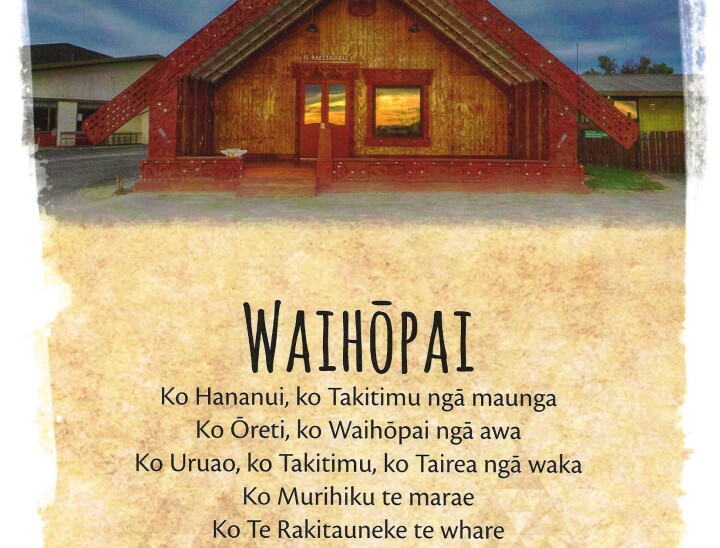

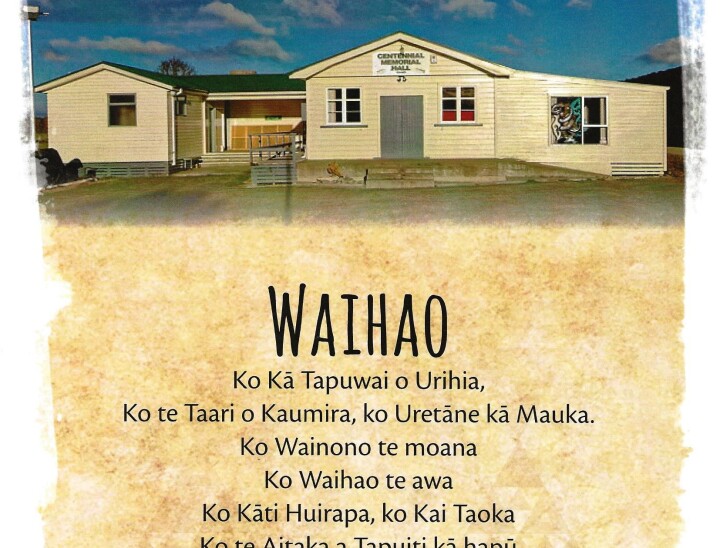

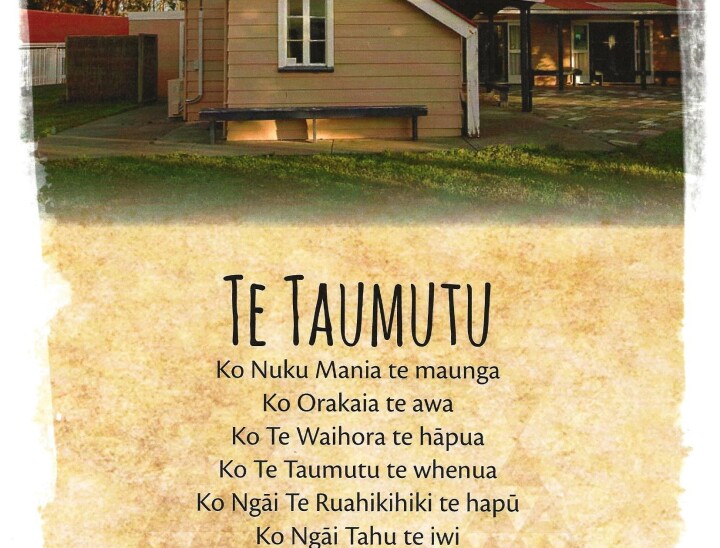

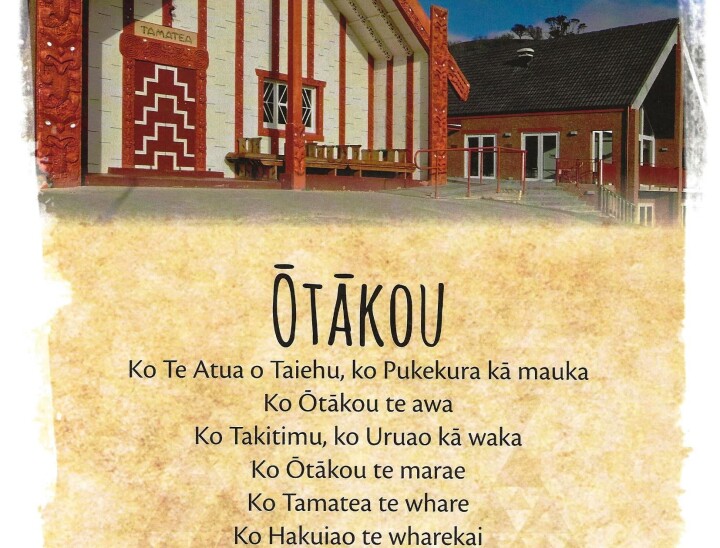

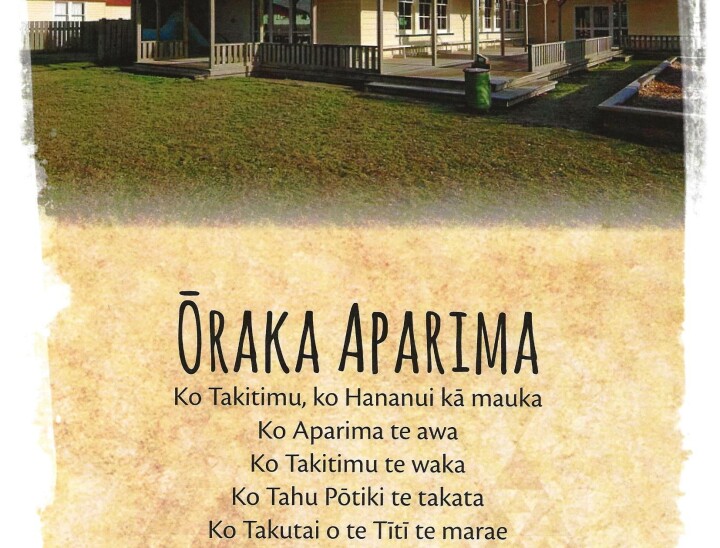

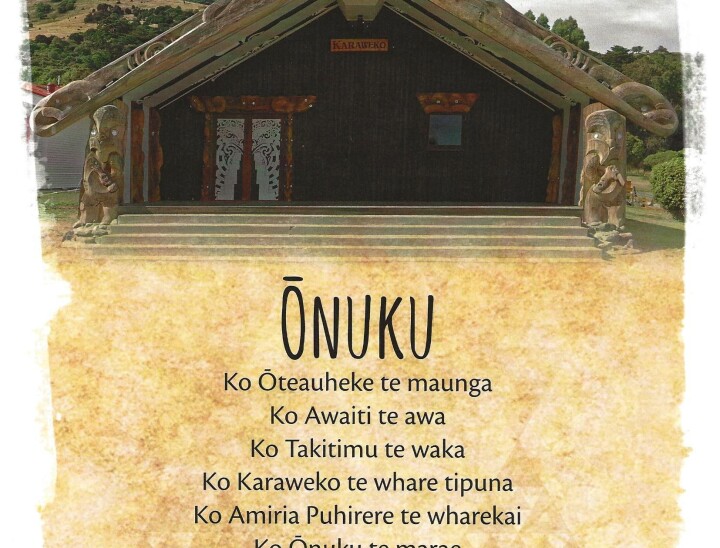

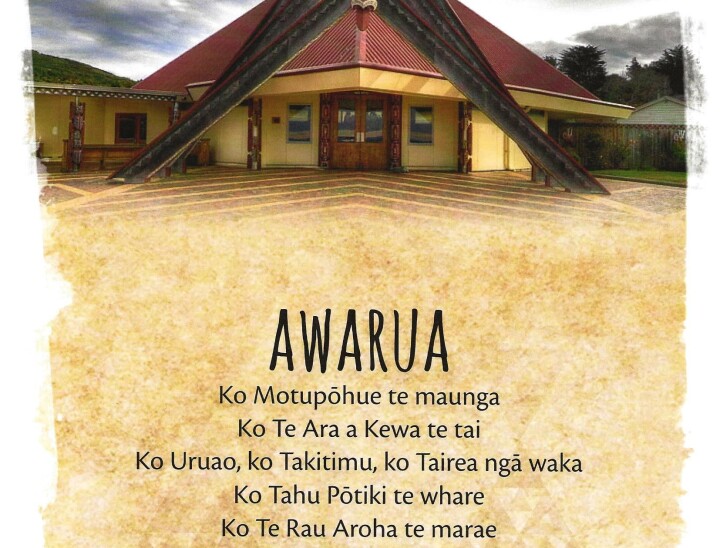

Ngāi Tahu Pēpeha

Below is a list of all Ngāi Tahu Papatipu Rūnanga Pēpeha.

I have included them all so you can begin to see the connections between Ngāi Tahu whānau whānui and our Ngāi Tahu whanaunga.

The six in which we as a whānau, have the strongest whakapapa connections with are:

* Awarua

* Ōraka Aparima

* Waihōpai

* Wairewa

* Ōnuku

* Kaikōura

And then of course there is Te Taumutu where we have a lot of our tīpuna at this urupā including Nanny Hinewai Thomas and her parents, Charles Morgan Thomas and our Kuia (Hinewai’s Mother) Te Amo May Epiha from our Ngāti Huia side.

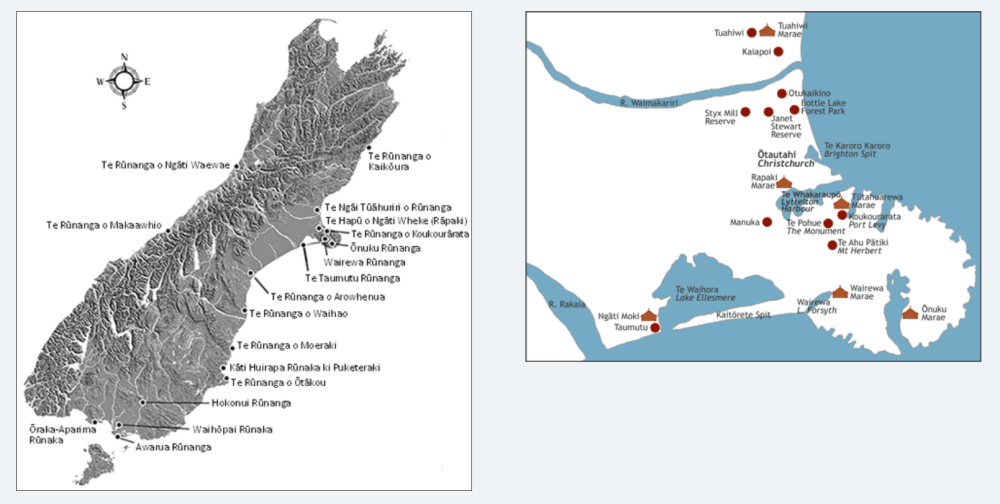

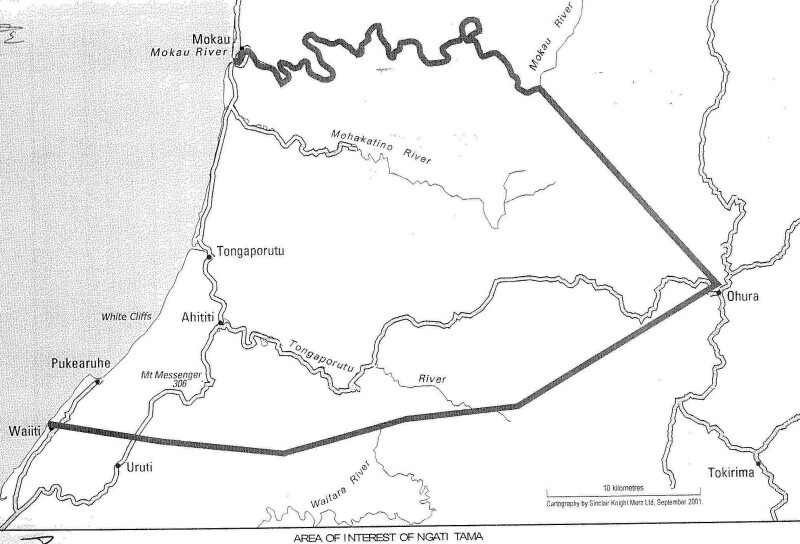

The map below (L) hand side, show the location of all 18 Papatipu Rūnanga, whilst the map (R) hand side shows the location of two of our marae, those being Wairewa and Ōnuku, it also shows Ngāti Moki marae at Te Taumutu where Nanny Hinewai mā lay in the urupā.